FINDING REVERENCE

One Piece #1: Lyn Risling’s Chéemyaach ik’ishyâat… (Hurry Up Spring Salmon…) @ the de Young

I had some choice words to say about the celebration of the revamped Arts of Indigenous America gallery at the de Young last week, which I shared in person over dinner with friends.

What I realized as I shared it is that I was overintellectualizing my feelings, which people do not really like. I think there’s a time and a place for discourse, but I’m noticing that dinner and maybe even Substack is not that time or that place. I think maybe I’m too used to the Ivory tower, and by that I mean wanting academic language to do social work, and I don’t think it does.

What I did notice was that when I instead talked about my love for two of the pieces in the new gallery, the tone of the room totally changed. Maybe I should have just written about that, I mused out loud to myself, and my friends in the kitchen did not disagree.

So here we are: one essay about one of two pieces I actually loved in the new gallery, on the day of the opening celebration, that made it worth all the initial distress.

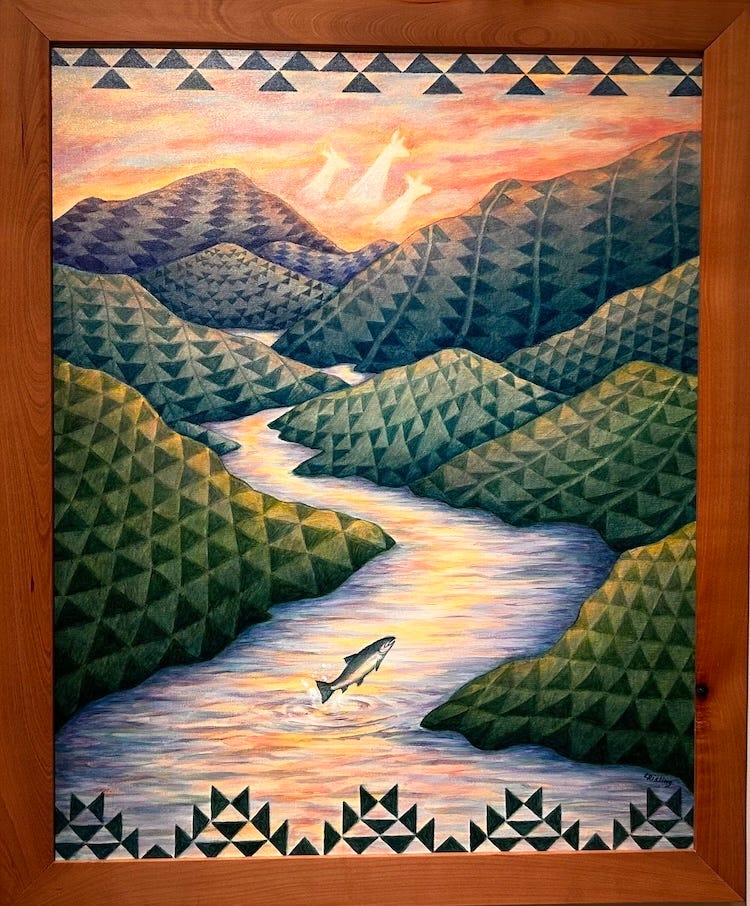

My favorite was this colorful painting by Lyn Risling entitled Chéemyaach ik’ishyâat… (Hurry Up Spring Salmon…). The combination of a bright orange/yellow sky and cool green/blue mountains simultaneously brightened and soothed. It was 100% giving the spirit of nature, but also a strong nod to the technique of craft. It’s in the marriage of these two traditions that the artist excelled — and in one fell swoop made the eons-old tension between the two disappear in an instant.

First off, this river! This rainbow channel as central to its silvery path. How inviting is this? How invigorating? When was the last time you felt that way about life? I should ask myself that! In my most confident moment, I’d say this water holds promise.

Next, let’s talk about this fish. The animal’s jump! So filled with glory. It’s almost a childlike energy, and I was not surprised to read that the artist’s lineage and current practice included illustration. If there ever were a main character of a children’s story, I’d want that fish to be it – the way it seems to have the whole world as spacious and open and available to explore. The river body it swims in continues on, just as friendly and as glowing and protected and shining for the rest of the way. How can you not feel excited for that salmon and its life ahead?

This whippersnapper captured my heart and transformed the landscape into something more playful than I’ve ever seen landscapes be able to do. Sometimes somber, or moody, or epic or lush, pastoral or perhaps even gothic landscapes can bring you in, but this feeling was different: it’s fresh, open, and also in motion, which led me down a whole different train of thought about the personality traits contemporary environmentalism assigns to the earth, and for what reason exactly.

Is Earth really a woman? Do we need to protect her? Or pacify her by not making her mad and find retribution through fires and storms? Sometimes this is what you hear about Mother Earth and her whims and her whiles, in conjunction with the request that we treat her better, since she is the bearer of all things we need.

Gendered language around the earth has lately struck me (and for a long time, many feminist/environmental thinkers) as oversimplified and therefore dangerous. In a recent trip up to the Headlands, I encountered a weird offshoot of this thinking when I went to an artist’s workshop that was ostensibly about a science fiction essay and making a sun print. Our instruction was to gather materials for the art project with one special rule: that we only take from the ground where the dead leaves or flowers had fallen. This was, we were told, important because we should make sure that we listened: if the bushes were ready to give us their fresh goods, they would have let that stuff fall. Instead, the instructor lectured, what’s dead is the offering and what’s alive is not ours.

Had the same person said it would be hard to justify picking living stuff off plants for a tote bag design, I might have agreed, but this incantation felt odd and misplaced. The landscape up there is endless, with almost everything already quite dry after the summer, and long dusty trails leading to a totally fresh and clean ocean just a mile away. This earth, if anything, was shouting JUST THINK ABOUT HOW MUCH YOU HAVE FOR ONE SECOND, and I don’t think it echoed with a request for atonement.

I don’t know what the Earth would say if it had a voice. But I think this painting portrays the world’s ecosystem as energetically different than a fragile thing that needs our protection, though also not something fierce that we have to control.

There’s the animal sun, not represented in one figure but instead with a group, so it might be less a sun and more an ancestry that lives in a realm above where we live. There’s also the self-awareness of the pattern at the top and the bottom: its stark print and dark color, a nod to tattoos, or bodies, or skin that’s otherwise absent. The triangle-printed mountains seem both soft and handmade. The pattern makes the mounds look like they are quilted, or as if a large blanket had been thrown over them all, giving them the sense of being both vast and all-encompassing, as well as soft and cozy. Going with the quilt reference, the fabric, at that scale, would be almost life-size, which brings the painting’s imagery in kind of close. The landscape, on the other hand, is sprawling and pushes away.

All in all, this painting achieves perfect balance without naming a war. There is no binary, and so it’s not gendered. It’s simply harmonious without explanation. In that is its brilliance. And also its gift.