DEEP RIVER

Artist's Date #50: Alonzo King Lines Ballet @ Yerba Buena

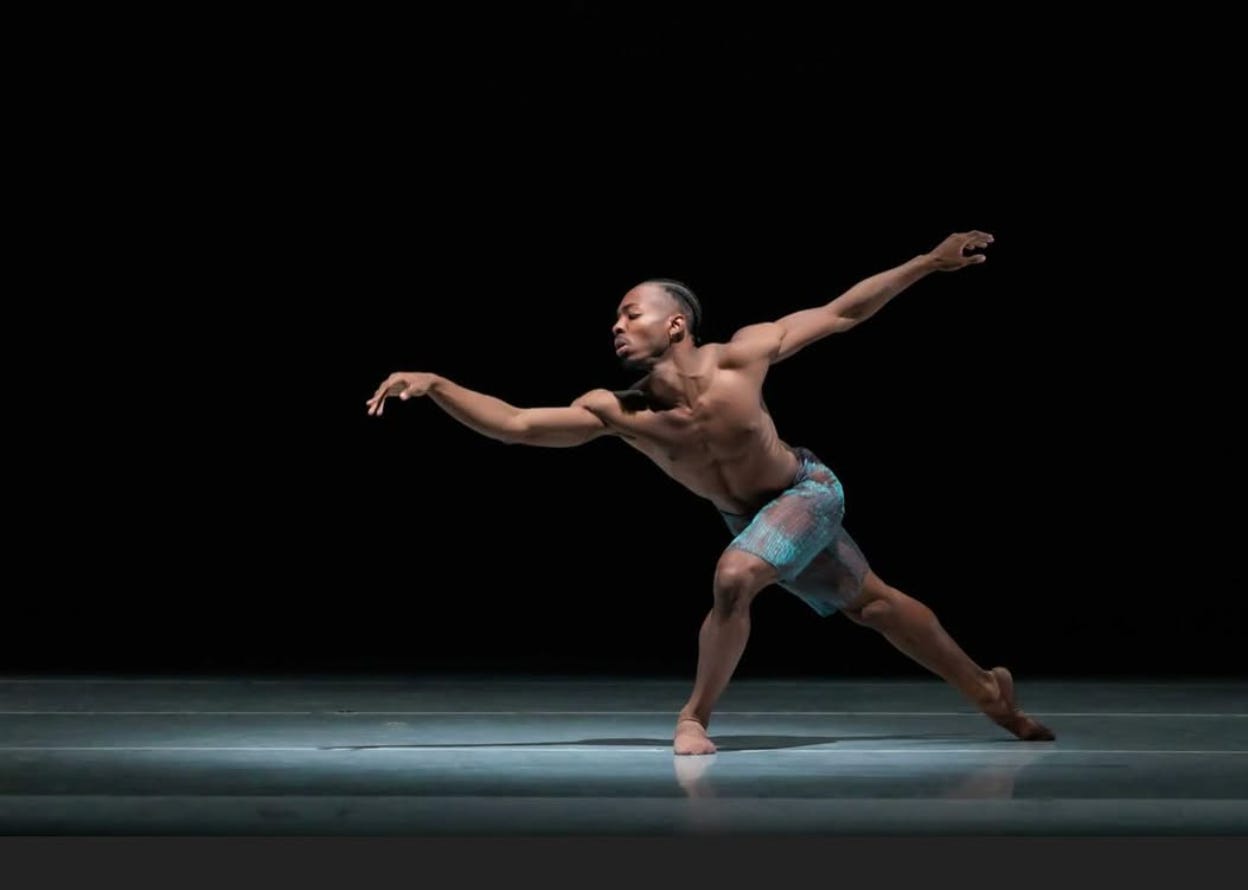

I had the chance to see the incredible Josh Francique perform in the Alonzo King Lines Ballet Deep River this weekend, and I’ve been thinking about him ever since. What was it that made me so emotional during his solo, during which I put my head in my hands and cried into them? It was some kind of surrender: his artistry was so great and his commitment so complete, I think I just admitted I’d never done anything with that level of either. But how on earth did he get to that place? I felt the dance piece itself, which I read as a commentary on the creative life, held some of the clues.

The narrative/performance began with one solo dancer amidst the rest of the company. She was standing in the light, with everyone else in slight shadow, and she brought her leg all the way up, the way dancers do. I immediately remembered how, in another dance show, at ODC theatre, a choreographer explicitly asked what one does with this level of talent. There was a screen behind the dancer, and as she did the same move, the word “prodigy?” (including a question mark) printed on top, alongside an arrow pointed toward her body. In Deep River, I read this move and siloing of one dancer as a way to place the “gift” at the start of the journey.

Somewhat relatably, the next step in the dance was an expression of agony. When I left the theatre after the performance was done, I walked out onto a live concert in the grass outside the theatre. The musician performing there happened to be explaining the very same thing about the song he had just sung: that the creative spirit dies a million deaths between the moment it shows itself and when it becomes self-actualized. So the hands near the head and thrashing movements in the soloists’ performances, I read as a kind of despondency — aorn awareness that you might have a gift and that alone really means nothing unless you can make use of it, and you don’t really know how!

The dance toggled between solos and full company dances, a format that was due in part to its creation during the pandemic. The impact of this back and forth was that I felt a story being made about the pursuit of excellence and the relationship of that vocation with the rest of the world.

At times, it seemed hopeful. One soloist would come into their dance with joy — a kind of breakthrough — but then the dancer would find that back in the group, though their joy was contagious, it still did not matter. When they were back on their own, performing that joy, they became exhausted and fell on the floor, with the rest of the group returning to energetically push the body (literally, the dancer rolled himself) right off the stage.

After that, I stopped paying so much attention. I think I was waiting for the moment when Francique would be dancing a solo. He has the kind of energy that is so bright that, even compared to the other dancers, who were also brilliant, he sparkled more. If he danced even slightly in front of any of the other company members, even if he was all the way to the side of the stage, all my attention was drawn toward him. At one point, I was thinking — of course, his solo is at the end. You couldn’t put him any sooner.

When it finally came to the moment when he took the stage alone, I just thought to myself in response to his movements: That’s it, he’s done it. But in reflection, I wondered what exactly he’d done? Mastered his own emotional struggles? Could it be that simple? If it were, then so many creative people might not spend so many years working in agony, which much of the dance seemed to state was a prerequisite.

So, I asked myself the question: What is the stage between experiencing the joy of your own craft and a full-on creative mastery? I felt it was not just practice, though that was involved. I realized that what I had seen was a decision. There was not a bone in his body that was ambivalent about what it was doing.

In an interview with him later, he said the artists who are really invested in the dance know that, as far as the beauty of it goes, the majority of it happens in the studio. He also said that he was taken very early on by someone saying that you can not expect to give 50% and get 100% of the results. And that he decided right then and there to see what happened with 100%.

Do even the best hedge on this bet? I think maybe sometimes. I got the chance to see a bit of the rehearsal the next day, before the next evening. On the stage, the dancers were taking a lesson with a rehearsal teacher. In one series of moves, she instructed the dancers to pirouette, but she also said practice. Pirouette practice. And in this moment, she noticed that Francique did one pirouette. And then she repeated her instruction, not the word pirouette, but the word practice. And then in the next part of the moves, when the pirouette came, he did two turns instead of one. Yes, she said, in agreement with how he’d taken her direction.

What I saw was that he was practicing the commitment – the repetition was about recommitting to exploring what’s possible for oneself within one’s own artistry.

Right after his solo in the performance, Francique went back to dance alongside the company. But unlike the other soloists, he danced with them…in unison. This struck me. Wouldn’t the reward for his commitment be that he stood out? In my own assumptions, I saw what I’ve been missing in my own creative process. I did not know that the gift wants you to end up becoming harmonious.