BINOCULAR PEOPLE

Life on the Whale Trail in Pacifica

I don’t know how I ended up on the Pacifica Whalespotting Facebook page but the frequent posts got me down to the coast, south of SF, children’s binoculars in hand. At first I just pulled over to the side of the road and joined a small group looking out at the ocean, passing around their own set of binoculars. Some would decline. It’s not everyone who feels the weight of a mammal that deep in our bones.

That night I posted:

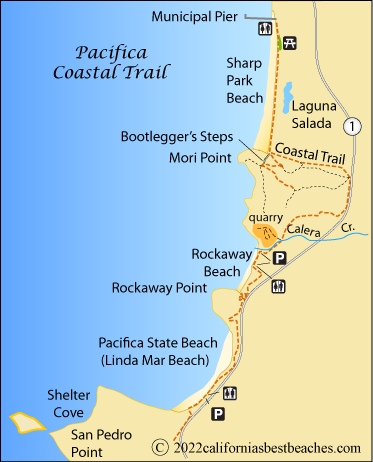

Incredibly playful bunch of whales just off of Mori Point around 2:30pm today! Just splashing and flipping and dancing around. I had my binoculars out on the path above Rockaway Beach. When I left there were still two active groups in the area though I’m not sure where the ones further away went off to.

May come back down with my daughter to see if the evening brings them back!

Not to worry, they’ll be back tomorrow. These last few weeks have been insane! one member said as a comfort.

Go toward Mussel Rock, another instructed. Gorgeous sightings too as they often travel north.

What I remembered about whale watching before this is a combination of sea sickness, cold, disappointment and my uncle’s small bead decorated cabin in Provincetown Massachusetts. That summer held a lot of other interesting things, namely bubble gum taffy from the shop of a thousand flavors and boys. My uncle worked at a bar his friend owned and his friend had a daughter that was a few years older than me and a million years more experienced. It was not my last crush on the type of guy who could be seen in the center of town at least once a day if one hung around long enough. If there was a summer to fall in love with nature over teenagers, that wasn’t the one.

It didn’t feel entirely necessary to bring Olive to the coast, her being only eight and not yet in danger of succumbing to a different kind of peer pressure but she agreed she was interested. We started where I had already gone on the weekend, Rockaway Beach, a tiny collection of seaside shops next to a small cove and seafood restaurant with a big lot. We parked just behind and saw the body of a whale from the car. Olive ran out and over the small dunes to get closer but for a while we saw nothing. A few minutes later, the whale emerged on the other side of the cove.

“Did you see the whale?” I asked another mom at the shore.

“Did I see the whale?” she asked, repeating my questions in a dry, almost mocking manner before answering “No, not yet.”

I had a hard time understanding her answer. They had clearly been at the beach for a while, her two boys tearing it up on the uneven sand on their bikes, while she watched on, facing the water. And we had just seen the whale from the car as soon as we parked; its body rising above the surface, with our bare eyes. I let it sink in that she was not interested in the idea of seeing the whale, even if I pointed in the direction of where we had spotted the spray.

The clarity came slowly, like I was refocusing on some truth I had refused to look more closely at before. It’s not enough that we’re both at the ocean with kids on a cloudy day, or that both our kids liked to bike ride, or that we were both mothers in California who liked to take our kids outside. We were not the same kind of person.

My parents were binocular people. I’ve never seen them both so happy at the same time as when they returned home from a trip to Acadia National Park after one week of birdwatching. They both thought the trip was so wonderful and they said so in their Brooklyn / Queens accent that replaces the er with an a. You’d think those two things alone, and in combination, would be enough to hold two people together but it wasn’t.

Olive moved toward the water and sat down looking toward the north end of the cove where the whale was now spouting, binoculars glued to her face. I pulled her away from her focus, saying that the FB page had noted five whales all together about four miles north. I didn’t want her to miss out on what I had seen the weekend before which had been a whale party: in my case three at once in close proximity slapping their tails around in what seemed like delight. As I drove us up the climbing coastline, the fog hung low and dashed over the street and I wondered whether in trying to give her something more I had taken something else away. She had already seemed brought in and embraced by the sight.

At the top of Muscle Rock the ocean stretched around us far enough below to imagine that we could live in the clouds. A man with a big brown sweatshirt had binoculars around his neck and said that he and his friend were looking for birds more than whales because that meant more fish. I told him about Massachusetts and vomiting and the whale boats and the disappointment and he told me that fifteen years ago they saw Hunchbacks only every once in a while and now they were everywhere.

Olive and I adjusted to our location and saw six or seven different whales at various points north of us, south of us and also dead center. We stayed until we got cold, screaming each time a whale tail splashed in the waves.

On the way home I stopped to get gas, and Olive asked whether I got the kind that was good for the environment, knowing that whales rely on clean air and fresh water.

“There’s no kind that’s good for the environment,” I said, and she stayed quiet for the rest of the ride.